If you search “learn to speak Urdu the right way,” you’ll probably find advice that sounds straightforward. Practice daily. Memorize vocabulary. Watch movies. Repeat phrases.

And yes… that’s all useful.

But here’s what doesn’t get said clearly enough: English speakers make very specific, predictable mistakes when learning Urdu. Almost everyone does. I’ve seen it repeatedly. And honestly, I’ve made a few of them myself when switching between languages.

Urdu isn’t just English with different words. It has its own rhythm. Its own sentence order. Its own way of expressing politeness and emotion. And when English habits sneak in, they quietly distort everything.

This guide walks through the most common mistakes English speakers make when learning Urdu and how to fix them in a practical, conversational way.

Why English Speakers Struggle With Spoken Urdu

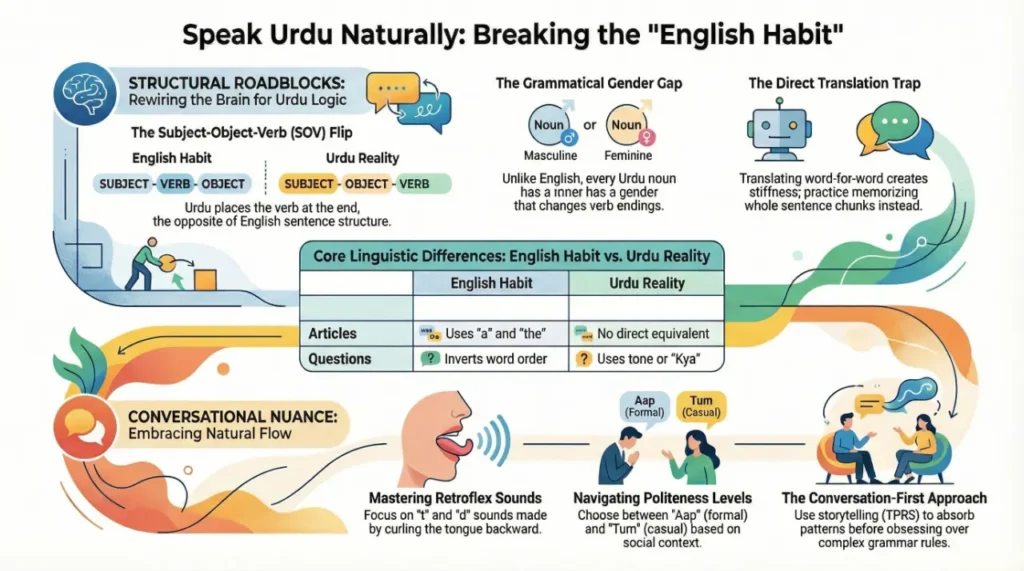

Before diving into mistakes, it helps to understand the core differences:

| Feature | English | Urdu |

| Sentence Order | Subject–Verb–Object | Subject–Object–Verb |

| Gender | Minimal gender usage | All nouns have gender |

| Politeness Levels | Limited | Multiple formal levels |

| Sounds | No retroflex consonants | Retroflex & aspirated sounds |

| Articles | Uses “a,” “the” | No direct equivalent |

That SOV structure alone changes everything.

In English, you say:

“I eat apples.”

In Urdu:

“Main seb khata hoon.”

(Literally: I eat apples.)

At first, it feels backwards. Almost unnatural. And learners often resist it subconsciously trying to “fix” Urdu into English patterns.

That’s the first big mistake.

1. Translating Directly From English

This is the most common problem. And probably the hardest to break.

English speakers often build sentences in English first, then translate word-by-word into Urdu. The result? Grammatically awkward Urdu that sounds unnatural to native speakers.

For example:

❌ Incorrect thinking:

“I am going to the market now.” → Translate each word directly.

You might end up overcomplicating it.

✅ Natural Urdu:

“Main ab bazaar ja raha hoon.”

Urdu doesn’t need filler words the same way English does. It often expresses ideas more directly. Trying to mirror English structure creates stiffness.

Fix:

Start thinking in Urdu patterns early. Practice memorizing whole sentence chunks instead of isolated vocabulary.

2. Ignoring Gender Agreement

Urdu assigns gender to every noun. And verbs change accordingly.

This surprises English speakers because English barely uses grammatical gender.

Example:

- Ladka (boy) – masculine

- Larki (girl) – feminine

Now look at verbs:

- Main thak gaya hoon.” (I am tired – male speaker)

- Main thak gayi hoon.” (I am tired – female speaker)

Many learners forget to change the verb ending. It seems small. But it’s noticeable.

And honestly, even intermediate learners slip here sometimes.

Fix Strategy:

- Learn nouns with gender from day one.

- Associate gender visually (imagine the object in context).

- Practice speaking sentences aloud to build reflexes.

3. Mispronouncing Retroflex and Aspirated Sounds

This is where pronunciation becomes tricky.

Urdu includes sounds that English simply doesn’t have. For example:

- ٹ (ṭ) – retroflex “t”

- ڈ (ḍ) – retroflex “d”

- کھ (kh) – aspirated k

- گھ (gh) – aspirated g

English speakers often pronounce these as plain “t” or “d.” Native speakers can instantly tell.

The difference between:

- “kal” (yesterday/tomorrow depending on context)

- “khal” (skin)

Is subtle but important.

This isn’t about perfection. It’s about clarity.

Fix:

- Listen more than you speak initially.

- Record yourself.

- Compare with native audio (preferably conversational, not robotic textbook recordings).

Sometimes learners rush into speaking without deeply absorbing sound patterns. Slowing down helps more than you’d think.

4. Overusing Formal Urdu in Casual Conversations

English speakers often learn formal textbook Urdu first. It sounds impressive. Polite. Very structured.

But everyday Urdu is softer. Shorter. More fluid.

Textbook:

“Kya aap meri madad kar sakte hain?”

Casual:

“Madad karenge?”

Both are correct. But context matters.

Many learners sound overly formal in friendly settings. It’s not wrong… it just feels slightly distant.

And then sometimes they swing too far and become overly casual. Finding balance takes exposure.

5. Struggling With Politeness Levels

Urdu has multiple ways to say “you”:

- Tum (informal)

- Aap (formal/respectful)

- Tu (very informal/intimate)

Choosing the wrong one can feel awkward.

English doesn’t prepare you for this distinction. So learners default to one form, usually “aap” for everyone.

That’s safe. But it limits natural expression.

Common Mistakes Summary Table

| Mistake | Why It Happens | Quick Fix |

| Direct translation | English sentence thinking | Learn sentence chunks |

| Gender confusion | English lacks noun gender | Memorize nouns with gender |

| Pronunciation errors | Missing Urdu sounds | Shadow native audio |

| Over-formality | Textbook exposure | Learn conversational patterns |

| Politeness misuse | No English equivalent | Practice situational dialogue |

6. Asking Questions the “English Way”

This one feels small at first. But it creates sentences that sound slightly off.

In English, we change word order to form questions:

- You are coming.

- Are you coming?

In Urdu, we usually don’t invert structures like that. We add “kya” at the beginning or rely on tone.

Correct Urdu:

- “Tum aa rahe ho.” (You are coming.)

- “Kya tum aa rahe ho?” (Are you coming?)

Notice something? The structure barely changes.

English speakers sometimes try to rearrange everything, or they overuse question words unnecessarily. It’s a subtle habit from English grammar rules creeping in.

Fix:

Think of Urdu questions as statements with a question marker not as inverted sentences.

7. Misplacing the Verb

Earlier, we mentioned that Urdu follows Subject–Object–Verb order. But here’s the thing: even when learners know that rule, they still accidentally slip back into SVO.

Example:

❌ “Main ja raha bazaar.”

(You can almost hear the English structure sneaking in.)

✅ “Main bazaar ja raha hoon.”

The verb comes at the end. Almost always.

At first, it feels forced. You pause. You hesitate. Maybe you even rearrange mid-sentence. That’s normal.

Rewiring sentence structure takes time because it’s not vocabulary it’s cognitive structure. Your brain wants efficiency. And English is its comfort zone.

Practical Strategy:

- Practice building sentences backwards.

- Start with the verb and construct from there.

- Shadow native speakers and repeat full phrases, not fragments.

8. Overusing Helping Verbs

English relies heavily on helping verbs:

- I am going

- I have eaten

- I will be working

Urdu expresses these ideas differently. English speakers often insert unnecessary helpers or overcomplicate tense structures.

For example:

English thinking:

“I have been studying Urdu.”

Urdu doesn’t always require the same layered tense construction. Simpler phrasing often works better:

“Main Urdu parh raha hoon.”

It covers the meaning naturally without stacking auxiliary verbs.

Sometimes learners try to make Urdu sound “advanced” by adding complexity. But simplicity is often more authentic.

9. Literal Translation of Idioms

This one is almost funny sometimes.

English idioms rarely translate directly into Urdu. If you translate:

“I’m feeling under the weather.”

Literally into Urdu… it won’t make sense.

Urdu has its own expressions. And they often reflect cultural context. Learners who translate idioms word-for-word create confusion even if grammatically correct.

Instead of translating idioms, learn Urdu expressions as independent units.

10. Focusing Too Much on Grammar Before Speaking

This might sound contradictory in an article about mistakes. But it’s important.

Many English speakers wait until their grammar feels “perfect” before speaking. They want correct tense, correct gender, correct pronunciation, everything aligned.

But spoken fluency develops through imperfect speaking.

Ironically, overthinking grammar can delay natural rhythm.

I’ve seen learners who understand Urdu grammar deeply but hesitate in simple conversations. And others who speak confidently with minor mistakes yet communicate better.

How to Speak Urdu the Right Way

If we simplify everything into a realistic learning framework, it looks like this:

- Learn high-frequency conversational phrases first.

- Listen daily before focusing heavily on grammar rules.

- Practice gender agreement in simple sentences.

- Record and correct pronunciation early.

- Speak imperfectly but consistently.

It’s not glamorous advice. It’s not flashy. But it works.

Why Conversation-First Learning Works Better

When you think about how you learned English as a child, it probably wasn’t through grammar charts. You absorbed patterns. You heard the same structures repeatedly. You copied tone. You made mistakes. No one handed you verb tables first.

Urdu works the same way.

This is why conversational immersion methods, especially TPRS (Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling) are incredibly effective for English speakers.

TPRS focuses on:

- High-frequency vocabulary

- Repetition in context

- Story-based interaction

- Listening before analyzing

- Speaking naturally, not mechanically

It might feel almost too simple at first. But simple is powerful.

The Biggest Speaking Mistake: Waiting Too Long

Some learners wait months before speaking. They think:

“I’ll speak once I’m ready.”

But readiness doesn’t come from silence. It comes from use.

In fact, conversational Urdu improves fastest when you:

- Repeat short story-based dialogues

- Retell simple stories in your own words

- Answer predictable questions daily

Not perfectly. Just consistently.

What TPRS Looks Like in Urdu (Practical Example)

Instead of memorizing isolated vocabulary like:

- jana = to go

- khana = to eat

- pani = water

TPRS builds a story:

“Ali roz bazaar jata hai.

Ali seb kharidta hai.

Ali ghar wapas aata hai.”

(Every day Ali goes to the market.

He buys apples.

He comes back home.)

Then the instructor asks:

- Kya Ali bazaar jata hai?

- Kya Ali school jata hai?

- Ali kya kharidta hai?

You answer repeatedly. The pattern becomes automatic.

No overthinking. No translation.

Just understanding and responding.

Conversational Fluency vs Textbook Accuracy

Here’s something slightly uncomfortable: textbook Urdu and spoken Urdu are not always identical.

Spoken Urdu is shorter. Softer. Sometimes incomplete.

Instead of:

“Aap kahan ja rahe hain?”

You’ll often hear:

“Kahan ja rahe hain?”

Context fills in the rest.

English speakers often speak in perfectly complete sentences. That’s not wrong. But it can sound overly formal in casual settings.

Conversational Urdu relies heavily on tone and rhythm. And rhythm only develops through listening and repetition.

Why Listening Matters More Than You Think

Many English speakers underestimate how much listening shapes speech.

You cannot pronounce sounds you haven’t fully absorbed.

Urdu rhythm especially vowel length and stress becomes natural only after repeated exposure. You start noticing patterns unconsciously.

And then something shifts.

You stop constructing sentences piece by piece.

You start responding.

That’s the moment when speaking feels different.

Conversational Mini-Dialogue (Natural Flow Practice)

Here’s a simple exchange that learners can repeat and modify:

A: Aap kya kar rahe hain?

B: Main Urdu seekh raha hoon.

A: Kyun?

B: Mujhe Pakistani culture pasand hai.

Now change it:

- Replace Urdu with Punjabi

- Replace culture with music

- Replace present tense with past

Keep the structure. Change the content.

This is how fluency compounds.

The Role of Confidence in Spoken Urdu

Sometimes the biggest barrier isn’t structure or pronunciation. It’s hesitation.

English speakers often pause before speaking because they are checking correctness mentally.

Native speakers don’t do that.

They prioritize communication first.

Accuracy refines over time.

And yes, you will make mistakes. But conversational momentum matters more than flawless grammar.

FAQ

How can English speakers improve spoken Urdu quickly?

Focus on conversational repetition, daily listening, and story-based speaking practice instead of memorizing grammar rules.

Is TPRS effective for learning Urdu?

Yes. TPRS builds fluency by repeating high-frequency words in context, which improves listening comprehension and speaking confidence naturally.

Should I learn Urdu grammar before speaking?

No. Begin speaking early with simple, repetitive patterns. Grammar understanding can develop gradually alongside conversation practice.

What is the fastest way to sound natural in Urdu?

Shadow native audio, mimic rhythm and tone, and practice short dialogues daily.

Final Thoughts

Learning to speak Urdu the right way isn’t really about eliminating every mistake. It’s about reducing the ones that block connection and letting go of the ones that don’t matter as much as we think they do.

English speakers often approach Urdu with logic first. Structure first. Accuracy first. And that makes sense. But spoken fluency doesn’t grow in perfectly organized steps. It grows in repetition. In half-confident sentences. In small corrections that happen naturally over time.

If you focus on conversation, storytelling, listening deeply, and speaking early even imperfectly your Urdu will begin to feel less translated and more lived. That shift is subtle. You might not notice it at first. But one day, you’ll respond without mentally rearranging the sentence in English.